Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures - Solving the plastics problem

By Sarah Greenwood MSc(Eng) FIMMM APkgPrf,

By Sarah Greenwood MSc(Eng) FIMMM APkgPrf,

Packaging Technology Expert/Leader, Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures, University of Sheffield

It has been a challenging couple of years for any manufacturer using plastic packaging, especially the bakery industry, which relies on the many benefits single-use plastics have to offer. No-one responsible for the specification of packaging can escape the pressure applied by customers and the public to do something about the 'Plastics Problem'.

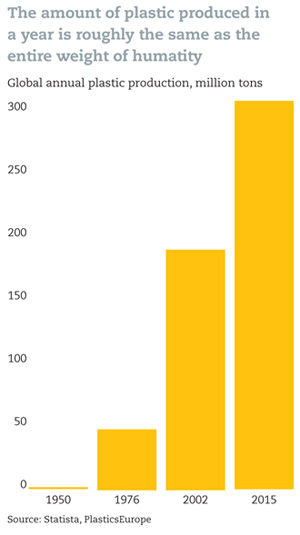

They clearly have a point. Worldwide plastics consumption has increased exponentially from 1.5 Million tonnes in 1950 to 348 million tonnes in 2017 (Source: Statista). This means that there are now over 8 billion tonnes of plastic in the earth’s system. To put this into perspective, if this amount of plastic were all converted into cling film, there would be enough to wrap up the entire earth with 25% spare. Through the mis-management of this plastic when it becomes waste, wildlife, our quality of life and even our health are being affected.

They clearly have a point. Worldwide plastics consumption has increased exponentially from 1.5 Million tonnes in 1950 to 348 million tonnes in 2017 (Source: Statista). This means that there are now over 8 billion tonnes of plastic in the earth’s system. To put this into perspective, if this amount of plastic were all converted into cling film, there would be enough to wrap up the entire earth with 25% spare. Through the mis-management of this plastic when it becomes waste, wildlife, our quality of life and even our health are being affected.

WHY USE PLASTIC AT ALL?

Plastic films used in packaging are lightweight and tough. They run efficiently on packing machinery, offer physical protection, a barrier against moisture loss, and for longer shelf-life products multi- layered films can be tailored to provide an air-tight seal and gas barrier to enable gas-flushing. Rigid plastics such as trays and 'acetates' offer protection for delicate products, enabling longer, more efficient supply chains, and offer visibility of the product inside when displayed in store. Even some card packaging components, such as u-cards, benefit from plastic coatings to give grease resistance.

However, as is well documented, the very properties that make plastics useful as packaging materials, also make them difficult to collect and process for recycling. Recycling rates for plastics lag far behind those of other packaging materials and it is the lack of progress in this area which is (partially) responsible for the plastics problem.

ARE BIOPLASTICS THE ANSWER?

The term bioplastic is so vague it can cover a whole range of materials, from bio- sourced, derived from plants to biodegradable materials.

Bio-sourced plastics can be biodegradable (e.g. PLA), or identical to conventional, durable oil-based plastics (e.g. polythene made from sugar cane). In turn, some oil-based plastics are biodegradable. The term biodegradable is not very helpful though, as most plastic will biodegrade to some extent given long enough. 'Compostable' is much more useful as there are recognised compostability standards for both industrial and home composting where the material must degrade within a specific timeframe. However, care needs to be taken if considering compostable materials. These can be the perfect choice for certain applications (ref WRAP) but they will only degrade adequately in the conditions they have been certified for, not in a landfill site or in the environment.

Bio-sourced plastics can be biodegradable (e.g. PLA), or identical to conventional, durable oil-based plastics (e.g. polythene made from sugar cane). In turn, some oil-based plastics are biodegradable. The term biodegradable is not very helpful though, as most plastic will biodegrade to some extent given long enough. 'Compostable' is much more useful as there are recognised compostability standards for both industrial and home composting where the material must degrade within a specific timeframe. However, care needs to be taken if considering compostable materials. These can be the perfect choice for certain applications (ref WRAP) but they will only degrade adequately in the conditions they have been certified for, not in a landfill site or in the environment.

Popular opinion is that bio-sourced plastics must be better for the environment than their oil-based equivalents, yet from a scientific viewpoint producing bioplastic requires a large amount of energy and it is not energy efficient to burn oil to manufacture plastics from plants when you could turn the oil directly into plastic. However, bio-sourced plastics do start to make sense from an environmental perspective when they have been sourced from waste biomass, rather than from crops grown specifically for that purpose. The amount of renewable energy used in their processing will also make a difference and we are currently researching this.

Even if you are willing to take the hit on cost and availability and can circumnavigate the technical challenges of introducing new materials, consumer acceptance is the key to its success of failure. In the paper, Understanding plastic packaging: The co- evolution of materials and society, we (Evans et al) illustrate this using the example of Frito-Lay's attempts to move to compostable cornstarch-based poly lactic acid (PLA) film for some of their potato-chip (crisp) packets in the US. An interesting feature of PLA is that it is much noisier than conventional film when handled which caused considerable consumer backlash. Frito-Lay has since moved back to conventional materials for these products.

SO, WHAT IS THE ANSWER?

Thinking of packaging as part of the system that delivers the product to the consumer rather than an entity in isolation is the way forward. This system includes not only the product value chain but where the packaging materials come from and what happens to them.

Thinking of packaging as part of the system that delivers the product to the consumer rather than an entity in isolation is the way forward. This system includes not only the product value chain but where the packaging materials come from and what happens to them.

It is sometimes hard to remember that doorstep recycling collection is relatively new in many countries. Up until then, most household waste was simply thrown away unsorted, in a linear economy. Recycling of packaging materials has developed over the last few decades, driven by EU legislation. Now, the EU is planning for a circular economy, where materials are kept in circulation by reuse and recycling for as long as possible before finally being disposed of.

To achieve this, packaging needs to be designed with recycling or re-use in mind. To close the loop, recycled material should be included in the packaging specification. There are challenges to achieving this, notably to do with the availability of post- consumer recyclate and food contact, but progress is being made in this field.

Systems thinking is not just about technical solutions, but also includes social and cultural factors. In the Evans paper we argue that gradual social and technical changes, such as the rise of supermarket shopping and women working outside the home, have been enabled by and in turn helped to enable the development of plastic packaging formats. The packaging forms an integral part of a complex system. Consequently, switching from plastics to an alternative material can create unintended problems – as were experienced with the crisp packet example above.

The adoption of reusable packaging systems is a hot topic at the moment and looking at how to make this mainstream is part of our work at the University of Sheffield. The bakery industry has already successfully integrated reusable trays into its infrastructure. Extending this to consumer packaging is admittedly a big ask, but there are opportunities, especially within food service – how about selling a lunchtime salad in a container that the customer brings back the following day for you to wash and use again? Or why not encourage them to bring their own container for their weekend croissants?

Plastic packaging offers significant benefits to bakery products, but how it is managed when it becomes waste is often unacceptable. Popular with the general public, bioplastics are not necessarily the answer and there are issues in simply swapping plastic packaging with another material, including food wastage and increased carbon dioxide emissions (Denkstatt).

A preferential methodology would be to implement systems-based thinking, looking at the supply chain as a whole rather than singling out the packaging itself. Co-operation of stakeholders across the entire value chain is key to keeping plastic packaging materials in the economy for as long as possible through reuse and recycling before disposal, creating a circular economy.

ASK YOURSELF WHAT CAN YOU DO AS A MANUFACTURER?

- Is a packaging component really necessary? Chances are you have already asked this question, have reduced the weight of your packaging and removed surplus components, but it should always be a priority to keep reviewing the situation regularly

- Check to see if your organisation or your trade organisation is signed up to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s New Plastics Economy Global Commitment (and in the UK, the UK Plastics Pact from WRAP). If you use a lot of plastic film, consider joining CEFLEX, a trade organisation that seeks to make packaging films more recyclable

- Work with the packaging professionals within your organisation, or alternatively, speak to a packaging consultant – just a couple of days' worth of their time could be enough to put you on the right track

- Specify your packaging with recycling in mind and seek to include as much post-consumer recycled content into your plastic packaging as possible, availability and food contact requirements allowing. *Recoup and *Recyclass have published design for recycling guidelines. (See links below)

- Consider reuse – are there opportunities to introduce reusable packaging systems?

- Always question environmental claims from material suppliers – ask for proof. Vague statements such as 'biodegradable', 'plastic free' and especially 'environmentally friendly' are nothing but greenwash unless supported by certification or evidence.

REFERENCES

https://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Considerations-for-compostable-plastic-packaging.pdf

Walker, S, and Rothman, R. "Life Cycle Assessment of Bio-based and Fossil-based Plastic: A Review." Journal of Cleaner Production. 261 (2020): 121158. Web.

Evans et al "Understanding plastic packaging: the co-evolution of materials and Society" currently under review.

https://ceflex.eu/

https://www.recoup.org/

https://recyclass.eu/

About the author

Sarah Greenwood MSc (Eng) FIMMM works on the UKRI funded project: Plastics: Redefining Single-Use at the Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures at the University of Sheffield. She is a packaging professional with over 20 years' experience working with plastics and packaging, much of it in the bakery sector. She is currently leading a proof of concept study into reusable packaging and also works as an independent consultant.

The Sheffield project is one of eight PRIF (Plastics Research Innovation Fund) funded projects – Papers from all of the projects are now available via www.ukcpn.co.uk/news/

For more information:

Sarah Greenwood MSc(Eng) FIMMM APkgPrf

Packaging Technology Expert/LeaderGrantham Centre for Sustainable Futures,

University of Sheffield

Email: sarah.greenwood@sheffield.ac.uk

3408